An age ago, Ric Ransom’s ancestors had a thriving inn on the bank of the Snoqualmie River near Carnation. Today, only the pylons of the pier that carried cargo up to their buildings remain along a rapidly changing riverbank.

What was once a busy family enterprise is slowly bring washed away by floods that seem to be getting worse and worse.

For Ransom, modern floods are unprecedented.

“130 years of information is no longer valid,” he said.

Ransom was among several dozen Lower Valley residents who put their questions to representatives of King County and Puget Sound Energy at a Sunday, July 26, meeting at the Sno-Valley Senior Center in Carnation.

“The reason we are here is because we are experiencing floods,” said meeting organizer and Carnation resident Bob Seana. Seanna was among residents who called for new data on all factors of Lower Valley flooding.

“Why do they want to lower the level behind the dam?” asked Fall City resident Marilyn Little.

PSE’s Jason Van Nort explained that lowering flood levels in Snoqualmie were part of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) mandate to PSE for improvements to renew its license to generate power at the Falls.

“What happens downstream?” Little asked.

The four foot dam at the Falls will be lowered by roughly half its height. The company is also removing about 5,000 cubic yards of fill from the riverbank alongside Plant 1. The Snoqualmie 205 flood control project, by contrast, removed about 50,000 cubic feet from the bank.

Based on the change in the amount of water stored at the falls, the PSE relicensing project is predicted to lower flood levels in Snoqualmie by six to eight inches, with a corresponding rise in the Lower Valley of about a quarter inch.

PSE modeled the downstream impact based on models developed nearly a decade ago by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers during the planning of the Snoqualmie 205 project. That project was predicted to reduce 100-year flood levels in the city of Snoqualmie by a foot-and-a-half, with a corresponding rise in the Lower Valley of about an inch-and-a-half.

“Granted, if that’s the inch that hits your house, that’s a big deal,” PSE Spokesman Roger Thompson said.

“It was,” replied Carnation farmer Erik Haakenson. He challenged PSE to be sure the Snoqualmie 205 project isn’t impacting the Lower Valley more than predicted.

“Many of us in this room believe anecdotally there was a huge difference, but we can’t be any more sure than anybody [else],” he said. “There has been no data collected.”

Haakenson called for clear evidence to be collected regarding the impact.

Van Nort later explained that, while it would be very difficult to measure the impact of development in the watershed on downstream flows, the company does use the 100-year-flood as its benchmark.

“When you’re looking at a flood like we had in January, and there’s literally water valley wall to valley wall, it’s very difficult to go out and measure,” said Joanna Richey, assistant division director at King County’s Water and Land Resources Division. “How do we know that it wasn’t five or ten inches? It’s virtually impossible to go out and empirically measure that increase. There are so many factors in a flood, to just go out an measure one” is next to impossible.

Richey echoed PSE’s stance that massive water levels in January had more to do with record flooding statewide than the 205 project. She cautioned that 100-year-floods can occur in any given year.

“We have had such extreme weather events, not just here but throughout Western Washington in the last few years,” she said.

Little was among several at the meeting wondering who was looking out for Lower Valley interests. Carnation resident Geary Eppley, the creator of the Valley-centric Floodzilla web site, asked who had oversight, and also questioned which Valley entities were involved in the planning

The primary regulatory body for the project was FERC, but about a dozen agencies were also parties of interest, according to Thompson.

A representative of King County Councilwoman Kathy Lambert attended the meeting. Lambert told the Valley Record that she has received a number of concerns from residents.

“We’re trying to get to the bottom of what we can do, to make sure the people of the Valley are as safe as possible,” she said.

The city of Carnation currently has no position on the issue.

Carnation City Manager Candace Bock said the project was approved in 2004 after a lengthy process. Neither King County nor Carnation had any permit authority over it.

The city council has not discussed the matter as a council, and there was no official presence at the Sunday meeting.

“We’re researching it,” Bock said. Kathy Lambert’s office is keeping Carnation in the loop on the matter, she added.

Seana called a second flood meeting for 7 p.m. Sunday, Aug. 16, also at the Sno-Valley Senior Center in Carnation. Technical experts from PSE and King County have been invited to share more detailed information on the project and its predicted impact. Seana asked participants at the meeting to each call 10 neighbors and pack the house.

Seana also called on residents to e-mail their flood data and experiences to help build a body of knowledge, to emlcarlson@aol.com.

“We’re looking for people who have experienced damage from the flood, or who will be experiencing damaging, even if there’s only a minor increase,” Seana said. People can also provide their addresses for an e-mail list for further postings.

River conditions

Twenty-three years ago, Carnation resident Robin Mason bought her farm on 310th Avenue from a family that had lived there three decades. The previous owners told her they had never seen floods get near the house or barns.

“In 1986, there was a pretty good flood,” Mason said. “We had water up to the buildings. I thought maybe these people were feeding us a line.”

But the prior owners’ daughter was still living in the vicinity, and she was shocked by the flood. Mason decided it must be a freak event.

Big floods followed in 1990 and 1995.

“Every flood was getting worse and worse,” Mason said. “Why is this happening?”

Flood data showed that the amount of water coming down the river wasn’t that much more than normal.

“It was where the water was going,” Mason said. “The water was not staying in the river anymore.”

The county had channelized the river in the 1960s. But since then, Mason concluded, parts of the river had filled with silt and gravel. She helped form a group called Citizens for Sensible River Management to do something about it. They worked before two years identifying problem spots before they were told that, due to endangered salmon, a gravel removal job in the river was a no-go.

“We need a plan for the entire Valley,” Mason said. “I think we need a dam above the falls. You can’t do it below the falls.”

She said PSE’s project “can only hurt us. It’s certainly not going to help us.”

High water

Carnation resident Debra Moery said she’s watched as flood levels at her home continue to rise.

“It’s supposed to be above the hundred year flood plain,” she said. “But there’s been 11 federal disasters since 1990.

“I’m not against PSE,” Moery added. “I truly want to believe that the PSE project might be the best thing in the Valley if the right questions are asked and if the project is transformed. Now is the time.”

The project should mitigate flooding “both upriver and downriver, for the largest percentage of PSE customers in the region,” she said. “It needs to mitigate flooding not just for one neighborhood.”

PSE should not base its project based on “old information,” Moery said. “There’s not way this can be a successful project. They don’t have the right information.”

For her, the increase to power generation in PSE’s plans don’t justify the effort.

“Why are they spending all this money to slightly improve something if they’re going to create catastrophic damage?” Moery asked. “Would government truly not care about everybody below Snoqualmie just to get one little project done?”

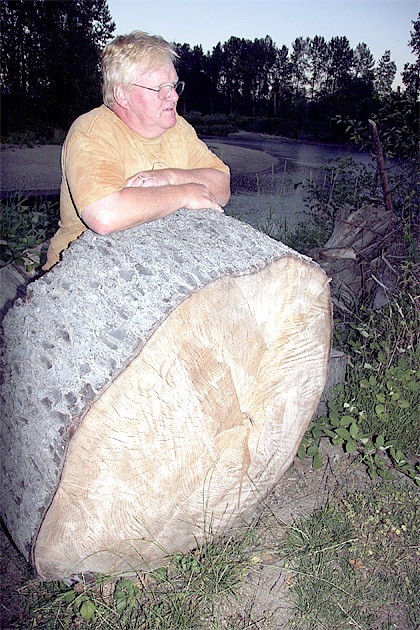

“I don’t need computer models,” Ransom said. “I can walk out to my front yard and be neck high in water, and I don’t need any more information than that.”

Ransom said it’ll take years for his property to recover from the last flood. Normally, he grows food on his six acres and donates it to area food banks and the Union Gospel Mission. But in January, the garden was washed away.

“They get nothing this year,” he said.

“I’m just a small guy,” he said. “Other farmers are losing acres of land.”

To Ransom, farmers are a dying breed, with little voice and few votes.

“I think the farmers in the Snoqualmie Valley are treated like the first Americans,” Ransom said. “Promises are made and never kept. We will flood you until you leave and give you no sympathy.”

“Don’t tell me your words, because your actions speak so loudly,” he added. “I’m only looking at what the results are. I don’t want to hear any words.”