Washington Democratic Sen. Patty Murray launched a “public process” this month to explore ways to make the Pratt River valley a federally-protected wilderness — an idea initially proposed by Republican U.S. Rep. Dave Reichert.

Reichert told the Snoqualmie Valley Record he hopes bills can be simultaneously submitted in the House and Senate in the next couple months.

Murray’s office said that no timeline exists for introducing legislation.

The proposal has broad support from conservation and recreational advocacy groups, including Cascade Land Conservancy, American Whitewater, Washington Wilderness Coalition and Sierra Club, and local politicians. Assembling a consensus of support should ease the bill’s passage through Congress.

“I believe that, politically, the obstacles have been removed,” Reichert said.

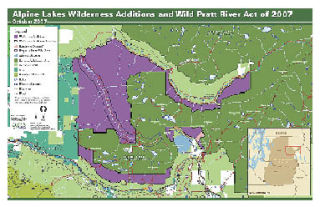

In 2007, Reichert introduced a bill to add the Pratt River to the existing 393,000-acre Alpine Lakes Wilderness Area. Congress excluded most of the river, which feeds into the Snoqualmie River’s middle fork, when it protected the lakes area in 1976. His proposal would add more than 22,000 acres and protect nearly 10 miles of the river as a federally-designated Wild and Scenic River.

The state has very little protected land in low-elevation valleys, such as the Pratt River valley, said Tom Uniak, conservation director for the Washington Wilderness Coalition.

The valley has ecological value, is a fishery resource and offers recreational opportunities, such as hiking and kayaking, according to Uniak.

Pratt River’s greatest value is its proximity to Seattle, said Tom O’Keefe, American Whitewater’s Washington state spokesman.

Reichert had difficulty finding cosponsors for his bill among his six Democratic colleagues from Western Washington during the previous Congressional session. The Democratic Party spent heavily in an unsuccessful attempt to unseat him in 2008.

It’s been easier getting bipartisan support since November’s election.

Reichert has already gained Democratic Reps. Jay Inslee, Adam Smith, Jim McDermott, Norm Dicks and Brian Baird as co-sponsors of his preserve-the-Pratt River legislation, which must be resubmitted in the current Congressional session.

There is no clear opposition to the proposal, which would only affect land already owned by the federal government. Access to the area would not change, and no major current users would be displaced.

But no one will say how long the bill could spend in Congress.

“Wild Sky took six years, but I can tell you, none of us expected it to take six years,” Uniak said, adding he hopes the bill will be passed during the current Congressional session.

Aides to Murray held working meetings earlier in February with stakeholders on the river’s future.

Local support has been critical to the bill, Uniak said.

“The reason people live, work and play in areas like Snoqulamie and North Bend is because [forests and rivers] are here,” he said.

Hunters “know where the 14-point bucks are coming from,” he said.

Murray’s office is pursuing a process similar to the one used during creation of the 106,000-acre Wild Sky Wilderness in eastern King County. After the House passed the legislation in 2007, Murray pushed it through the Senate last year.

Pratt River could reacquaint the public with the Wild and Scenic River Act as a tool for preservation, O’Keefe said.

Passed in 1968, the act is meant to preserve the free-flowing character of a river. It doesn’t carry the same restrictions as federally-designated wilderness or park land, and the different designations can overlap, such as in the current Pratt River proposal.

“This is a tool that definitely hasn’t been used as well as it could’ve been” in Washington, Uniak said.

Washington has six rivers designated as “wild and scenic,” while Oregon has 48 such rivers.

“You’d be hard-pressed to say Oregon has six-times more scenic rivers than we do,” he said.