Alexander Anderson is no head-in-the-clouds academic.

On paper, he may seem like one, having graduated high school, earned a bachelor of science degree, started classes for his master’s degree, accumulated a stack of research for his doctorate, surpassed a theoretical limitation on electricity production, and started a company, Odin Energy Works, all by the age of 18. Alexander, though, knows how to talk to people, and when to go easy on his non-scientific audience.

“This is just math,” he tells me on a recent sunny day at his North Bend home. He clicks through slides of a presentation he’s giving at a science symposium Nov. 1 in Everett. The screen fills with mathematical equations, 10 or 12 characters long, not one of them a number. “More math, more math,” he continues, then finally, words.

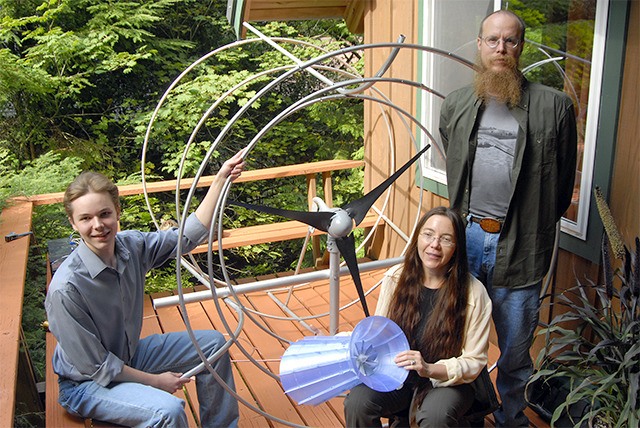

“First, you have the Betz limit,” he says. That’s the highest level of efficiency you can expect from an open-rotor wind turbine, 59 percent. Anderson, with help from his parents, Alex, a mechanical engineer and aircraft and inspector, and Olga, a consultant, started trying to beat Betz “a long, long time ago,” he says, when he was 14.

Why? “When you’re inventing, you’re struck with a notion,” says Alexander. “You think ‘what if?’ You think about it and think about it, and get this visual picture. And then, you need to go test that!”

Experiments were always part of Alexander’s home-schooling, explains Olga, but by then, the family was enrolled together in college; at 14, Alexander was too young to attend alone. They all graduated from St. Martin’s University last spring. Building and testing the prototype wind turbines was “something for us to do as a family,” she said.

Alexander decided the turbine needed an augmenter—a sort of flared opening added to the narrow end of the cone-shaped turbine—and calculated the formula that could reliably indicate the turbine’s output. “That was Alexander’s accomplishment,” says Olga. Augmenters had been done before, added Alexander, “but the reason you don’t see them everywhere is that it was impossible”—Olga interjects “nearly impossible”—“nearly impossible to predict what they would generate.”

Test flight

To test Alexander’s augmenter calculations, they built small-scale versions using a 3-D printer, and tested it, variously by running a computer fan over it and by holding it out the window of the car as they drove. Eventually, they attached the full-size version to two blimps, running test flights of their patent-pending prototype, A-Pegasus, at Olallie State Park, and at Puget Sound Energy’s Wild Horse Wind Farm. See the video at www.youtube.com/channel/UCFd7gTRIdOH-L2Cjbn4NwjQ.

The flights were successful and Alexander is now working toward certification for A-Pegasus. It’s a complicated process, requiring at least six months of accumulated data, which he’s collecting this winter with a ground-mounted version of the turbine.

A balloon mounted wind turbine has some practical limitations: “You can fly in rain, but not in snow,” says Alexander, because the weight of the snow accumulates on the blimps, pulling them down; the turbine has to be grounded in very strong winds; and helium for the blimps is expensive, so he switched to hydrogen, because he can make his own. It has one big advantage, though, in that it’s small.

“The idea is you have lots of places that have good wind, but not much grid connection,” says Alexander, like in Papua, Guinea. There, people can use A-Pegasus to charge a battery bank (four 12-volt batteries charge in about an hour), and then use the batteries to power whatever they need.

Inspired by the success of A-Pegasus, the family, as Odin Energy Works, visualizes a small hydropower turbine project some day. They talk wistfully about X Prizes (cash awards for major scientific achievements, www.xprize.org), and often, about another unbreakable limit, calculated by Peter Jamieson. He found the efficiency limit, 88 percent of an augmented wind turbine.

“When people say ‘it can’t be done,’ we tell them to talk to Jamieson!” says Olga. She’s moved by the spirit of invention, and wants more people to be, too. “Our sponsor said the inventing and engineering motive is just asleep in many people,” she said. “I’m sure there’s many people like us with engineering educations… I think it’s important that people don’t just watch TV, but do things!”

Olga is now pursuing her doctorate, Alex continues his career at Boeing and Alexander is in Washington State University’s online electrical engineering management program. He presents his research on A-Pegasus at the Innovation @ the Edge conference, Nov. 1 at Future of Flight in Everett.

Alexander Anderson assembles his A-Pegasus wind turbine inside his garage.

Version 2 of Alexander Anderson’s wind turbine, now under construction at his North Bend home, will probably be green, so, combined with the blue balloons he used to fly it, A-Pegasus will wear Seahawks colors.