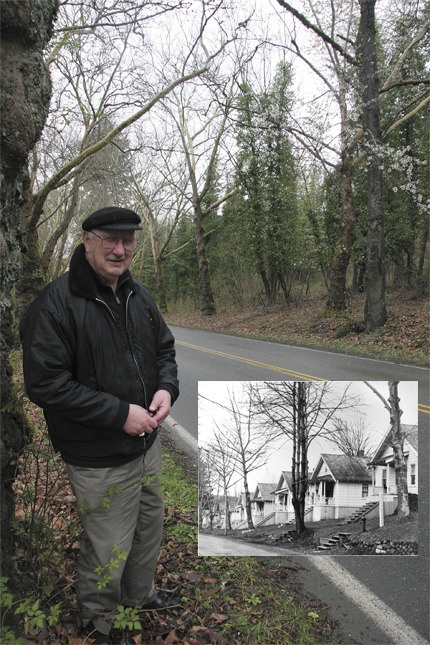

Visit the Reinig Road Sycamore Corridor, a registered King County landmark, today, and you will see rows of huge, stately trees, forming a natural cathedral of arching branches and thick trunks.

But a visit with North Bend resident Harley Brumbaugh, armed with an old black and white photo, reveals a very different place.

The corridor of trees was once the Riverside neighborhood, part of the lost community of Snoqualmie Falls built around the now-closed Weyerhaeusere mill. Seven decades ago, Riverside looked like any other suburban neighborhood, with houses set back from younger, smaller sycamores, reached by concrete steps. Today, only the trees remain.

Riverside Rats

Brumbaugh grew up in Riverside. Son of a steam shovel operator and a homemaker, he roamed the streets and meadows of Snoqualmie Falls with the boys from his neighborhood.

“We called ourselves the Riverside Rats,” Brumbaugh said. “It was a Tom Sawyer existence.”

The boys used a chicken coop for a club house. Bylaws included “No girls allowed.”

Living in Riverside meant more freedom for Brumbaugh and his pals than most children in Snoqualmie Falls. They lived closer to the more urban environment of Meadowbrook than anyone else, so the boys were able to collect old beer bottles and sell them back to the tavern owners across the river.

“Kids who lived in the Orchard, on the other side of the mill, they were sort of confined,” Brumbaugh remembered.

Every Thanksgiving, boys from the two neighborhoods faced off in a touch football game. The boys had to mind their own fouls, because there was no referees.

We had great freedom as kids,” Brumbaugh said. “But we all worked. We were expected to produce for the family.”

Brumbaugh was expected to pick vegetables and fruit in the summer, and keep the family wood pile stacked year-round. He and the other boys also helped elderly residents with their firewood.

“We had the meadows, we had swimming, fishing,” Brumbaugh said. “We had each other. It was very close. Nobody really screwed up. Our fathers worked together and our mothers knew each other. I can’t remember the police ever coming.”

At the time, Snoqualmie Falls was bigger than North Bend or Snoqualmie.

“We felt as though we were in a community,” Brumbaugh said. “We had all the facilities.”

Every student that attended the Snoqualmie Falls Grade School knew each other, though enrollment fluctuated with employment.

“We got superior ratings in music,” Brumbaugh said. “It was because we had roots. We knew who we were.”

Youth life

Setting the standard for youth behavior was Harold Keller, the director of the community hall and YMCA in the mill town. If a teen goofed off too much, he might find himself a persona non grata at the Y.

“There went your social life,” Brumbaugh said.

Harold’s son Ward Keller remembers his father, who ran the YMCA from 1942 to 1965, as an energetic, hard-working man.

As company photographer, “he was always on the spot for any community activity.”

Keller used his father’s massive collection of negatives as the basis for his book, “Vanished,” a history of the mill town, which he published three years ago.

Young people learned everything from knitting to rifle marksmanship at the YMCA. The senior Keller used the rivers of the Valley to teach swimming to children who didn’t have access to a pool. He went to the Arthur Murray studios to learn the latest dance steps, then taught them each year to junior high school students.

Everyone that lived or worked at Snoqualmie Falls was a part of the YMCA and its recreation. Keller said he was amazed by what that meant for young people,

“We never had any problems with kids during that time,” he said.

Sound of the mill

Brumbaugh was in the last class to graduate from Snoqualmie High School. Mill students went on to attend junior high in North Bend and high school at the newly-founded Mount Si High School in Snoqualmie.

Brumbaugh had his tonsils and appendix removed at Snoqualmie Falls Hospital.

“I spent my time in the men’s ward,” he said. “The elevator was like a freight elevator” — a bit wobbly.

During one stay, his teacher walked across the street to visit.

“I could not believe that my teacher would come to visit me,” Brumbaugh said.

The hospital, school and YMCA, and the attendant hotel, barber shop and store all overlooked the gigantic mill and its smokestacks.

Brumbaugh recalls the ambience of sound to the place.

“You could always hear the whining and the clank-clank of lumber going through,” he said. “There would be percussive jabs of whistles. The main mill whistle was a baritone — a low ‘wooh!’ You expected those things. You could see the cinders on your windowsill at school.”

An aspiring professional musician, Brumbaugh saw a different world when he commuted to Seattle for trumpet lessons. But he always appreciated the mill’s sense of unity.

Lives were regulated year-round by the sounds of the mill.

“We got up by the whistle, caught the bus by the whistle, came home at noon by the whistle,” Brumbaugh said. “Everybody had the same regimen.”

Deep impact

To many longtime residents, the vanished mill town was clearly the strongest influence on the Valley of the last century. The mill’s economic engine drew workers from as far as Redmond, coalescing a community.

“The biggest employment was the mill and the woods,” said Keller said. “”You had four or five generations working at the mill. It really impacted the whole area.”

The community of Snoqualmie Falls began to shrink in the 1930s, and was completely gone by the early 1970s, as homes and services moved out into the greater Valley. The mill itself closed as the local sources of lumber were exhausted.

“There was a slow transition,” Keller said. “They could tell exactly how much timber they have. It took 20 years to really finish off the big logs. Once the timber is gone, there’s just not many logs going out of the area.”

Keller went away to college in 1950.

“I was gone before it was gone,” he said. “The thing that always impressed me was the camaraderie. Today, anybody you talk to wishes they could raise their kids in the same environment with the same facilities.”

“Weyerhaeuser was generous to the families that dedicated their lives to it,” Brumbaugh said. Widows were supported, and children encouraged to attend college.

The sense of unity that the town created is something that Brumbaugh still yearns for.

“It’s a feeling you can’t really shed.”

That small community deeply mourned the 128 men who died serving their country in wartime.

“It was an extended family,” said Brumbaugh, who played Taps when the soldiers came home to their final resting place. “Maybe I was too young to do it, but there was just this feeling. We felt the sacrifice.”

Most people grow up and leave their communities behind. To Brumbaugh, “Snoqualmie Falls left us.”

He recalls when his parents moved their home across a temporary bridge to Snoqualmie in 1958, part of an exodus of ninety dwellings that year.

But the change didn’t really sink in until he was home visiting as a serviceman.

“I remember driving under the trestle, and — they’re all gone,” Brumbaugh said. “The hospital was gone. You could still see where the roads were. It was like the twilight zone. My God, where’s my home?”

Brumbaugh still gets a lump in his throat when he drives through the sycamore corridor.

“I can tell you the families that lived behind each of the sycamore trees,” he said. “Our house was the first house you would see as you enter the community. And it’s gone.”

To Keller, the loss of the YMCA at the mill left a 45-year gap in recreation for Snoqualmie residents.

“Hopefully, this project they have at the Ridge will be the beginning of restoring the YMCA’s efforts,” he added.

New future

After years of stagnation, the mill site’s future now appears to be entering high gear. Entrepreneurs Greg Lund and Bob Morris are currently negotiating with Weyerhaeuser for purchase of the mill property, with an eye to open Ultimate Rally Experience, a driving course, corporate training center and film location.

Their purchase does not include the entire former mill town. Weyerhaeuser retains some of the former town sites, while others are privately held.

While little discussion of the old town has been taken place, Ultimate Rally Experience is aware of the site’s past.

“History is a big deal and it’s very important to me,” Morris said. “We have plans to preserve anything and everything historic on the site as time goes on.”

Museum exhibit

The story of the Snoqualmie Falls mill and community is the primary exhibit for 2010. As the museum opens this month, it will feature the history, images and story of the mill town and its impact on the Valley.

As part of that focus, the museum is reprinting “Memories of a Mill Town – Snoqualmie Falls, Washington 1917 to 1932,” by author Edna Hebner Crews.